Adelaide A. Hebert, MD, with Lisette Hilton

Photo by Randy Gay/McGovern Medical School at UTHealth Office of Communications

Hyperhidrosis has tremendous impact on the full scope of pediatric life and well-being.

I find that young children who experience excess sweating are most hampered by the excess moisture on their hands. A telling example is that no one in preschool or kindergarten wants to hold these children’s hands when they are crossing the street or playing Ring Around the Rosie. This rejection really hurts their feelings.

Their artwork and paperwork get wet, and teachers often berate them, not realizing that they suffer from a causative medical condition. Children who use a computer at an early age find that challenging because of the wetness of their hands.

Older children become more self-conscious as they realize they are different from other children. Their paperwork, musical instruments, and sports equipment often get wet. They feel they cannot do what other children with normal, not excessively sweating skin can do.

These children get teased and bullied about hyperhidrosis. They may also have axillary hyperhidrosis, which limits the clothing choices they have. The axillary sweating renders them reluctant to raise their hands in the classroom. Parents often feel guilty, particularly if they had hyperhidrosis themselves in that they could potentially have passed this condition on to their offspring. As you can see, this patient population faces a whole host of challenges.

What we can do to help

When to start therapy is not so much about a child’s age in terms of numbers. Instead, consider the impact on the patient’s life.1

I will start treatment in a child as young as 5 years of age if I really feel it is indicated and is in the child’s best interests. The decision to initiate therapy really depends on the individual patient; the overall impact on the patient’s life; what the parents want; how the patient tolerates therapy if it is initiated; where they live; whether they participate in sports or play musical instruments. All these factors come into play.

We have a host of therapeutic options that include glycopyrrolate (Robinul). This anticholinergic agent is probably my number-one recommended treatment. This drug is generally well-tolerated by children. But we must guide patients in the safest use of this medication for their child’s hyperhidrosis. For example, if patients on Robinul are running for gym class or soccer or a cross-country team and they get overheated, they may have great challenges. We warn them about the risk of overheating. We also encourage them to discuss potential medication side effects with their PE teachers and coaches so they, too, are fully apprised that children on this medicine may not sweat enough, and these children should cool themselves down if they are doing extensive outside exercise.

In general, I begin a slow titration of Robinul over a few weeks, starting as low as 1 mg in the morning and 1 mg at night. The patient might increase the dosage by 1 mg each evening until they feel they have good control and, hopefully, not too many side effects. I do tell my patients that if they do not wish to take Robinul on the weekends when they are at home and not sweating that much, that is fine. I also tell them in summer months, when we have a considerable amount of heat, they may need to take an extra pill. These patients can learn over time to self-titrate.

If a patient grows taller and gains weight, we will need to increase the dose.

Oxybutynin is another treatment that is widely used in pediatric patients to treat bed-wetting and can be used to treat hyperhidrosis.

If a patient is 9 years of age or older and has axillary hyperhidrosis, we can use a new anticholinergic formulation called glycopyrronium tosylate (QBREXZA, Dermira). This is a towelette that patients apply once daily.

Patients should carefully wash their hands after use, so they do not inadvertently transfer residual medication to the eyes. If they do, the medication can dilate their pupils, which can make it difficult to see and make physicians or other health care providers believe they have more serious challenges going on than just hyperhidrosis and a side effect from a medication to treat hyperhidrosis.

I occasionally combine oral treatment with extra-strength antiperspirants, but I acknowledge that many of my colleagues feel that might result in too much anticholinergic impact. We want patients to be able to sweat to cool their core body temperature when necessary but not sweat excessively.

Every patient is a little different, and finetuning the therapeutic strategy can be very helpful and result in few side effects. That has to be done with forethought and a compliant patient.

Listen, learn, and do not dismiss

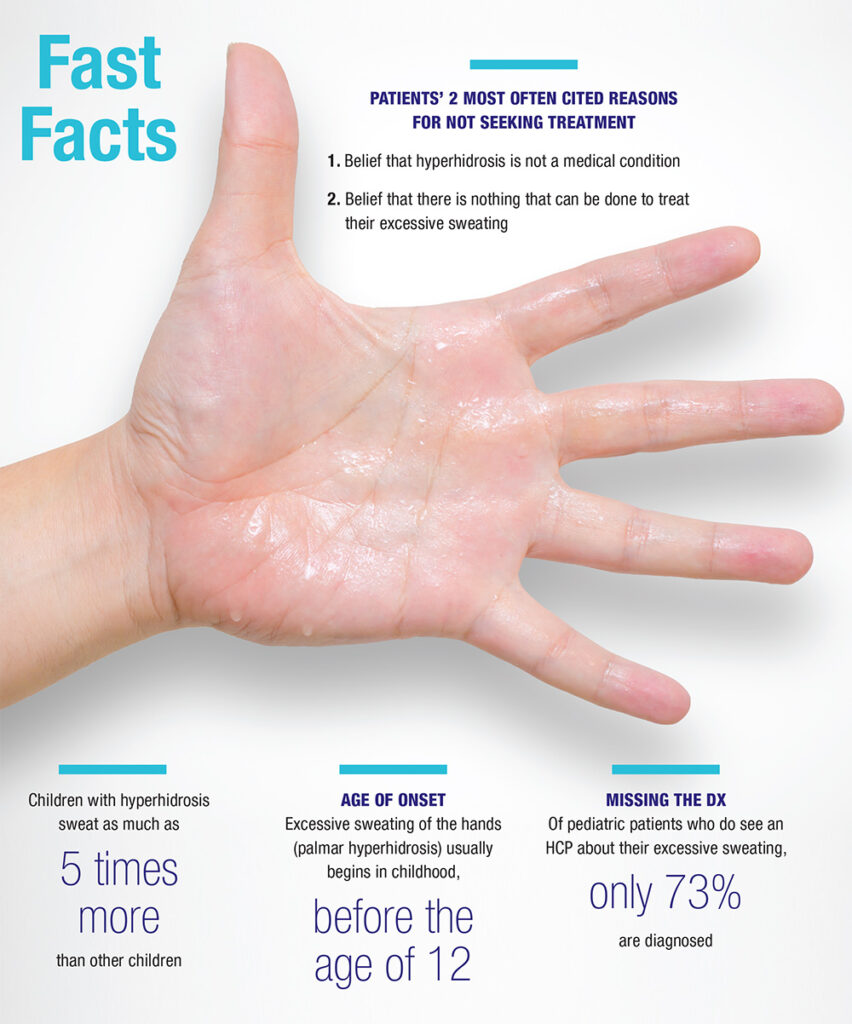

Many physicians either do not recognize hyperhidrosis or dismiss the condition as being “normal,” which causes more emotional harm for the patient. These patients might be reluctant to approach another health care provider with the problem because of their disease state being downplayed.

We recommend that patients and physicians go the International Hyperhidrosis Society website, SweatHelp.org. (I am on the Board of Directors of that organization and have served in that capacity for more than 15 years.) This website offers a tremendous amount of information for patients, as well as products that can help patients sleep, function, and wear clothing and socks without worrying about resultant staining from hyperhidrosis. We also have a school nurse outreach program within the International Hyperhidrosis Society, through which we have sent samples

of extra-strength antiperspirants, which can be very helpful for children suffering with excessive axillary sweating. The school nurse outreach program helps educate nurses about the condition.

Early recognition and early intervention can help these patients with hyperhidrosis. These patients are grateful when we acknowledge their hyperhidrosis as a medical condition and initiate a beneficial therapeutic option.

On the horizon

Emerging treatments include one that we are studying in an ongoing clinical trial. This medication is yet another topical agent that is an anticholinergic gel formulation. The investigational product looks exciting, but I do not yet have any data to share because we are still in the preliminary stages of the research.

Hyperhidrosis is coming of age. People are beginning to realize that this is a condition that warrants therapy, many suffer from it, and drug development to treat it has value.

We are learning more about the condition in children. We have done recent research with the International Hyperhidrosis Society and are beginning to realize that the impact on small children is substantial. In fact, small children may not fit the mold that we have typically identified for adolescents, young adults, and adults. Young children seem to sweat during sleep, which was probably underappreciated previously.

We also were classically taught that hyperhidrosis in small children was primarily palmar, but now we are finding that these children have sweating on the palms, soles, and sometimes in the axilla.

REFERENCES

- Remington C, Ruth J, Hebert AA. Primary hyperhidrosis in children: A review of therapeutics. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021 Mar 4. doi: 10.1111/pde.14551. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33660889.

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Hebert reports no relevant financial interests.