Multiple morphologies

With Katelin A. Harrell, MD, and Jarad Levin, MD

CASE HISTORY

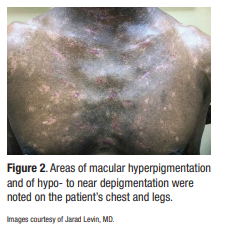

A 48-year-old Black male patient was referred to the dermatology department at the University of Oklahoma Health Science Center by a church-affiliated free community clinic. The patient, diagnosed with “vitiligo” since his incarceration some 13 years earlier, had now developed additional cutaneous findings. Most prominently, he demonstrated non-tender, non-pruritic red-brown firm plaques and nodules that began on the scalp and subsequently spread to the face, neck, trunk, and extremities (Figure 1). He also showed some areas of macular hyperpigmentation and striking areas of hypo- to near depigmentation on the chest and legs (Figure 2). Various over-the-counter creams had not improved the skin lesions. A review of systems revealed unintentional weight loss and dry eyes. He specifically denied fever, cough, shortness of breath, chest pain, fatigue, arthralgia, or neurological symptoms.

The patient’s other health issues included poorly controlled type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and asthma. Although unemployed at the time of his visit, he had previously worked as a delivery driver. He denied current and previous alcohol abuse, smoking, or illicit drug use. There was no personal or family history of autoimmune disease.

Over the course of his evaluation, an extensive diagnostic workup revealed an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein and significant vitamin D deficiency. Serum calcium was normal; chest x-ray and electrocardiogram were also normal. Several skin biopsies were performed from different morphological lesions (face and leg). The differential diagnosis was rather broad.

|  |

What do you think he has?

DISCUSSION

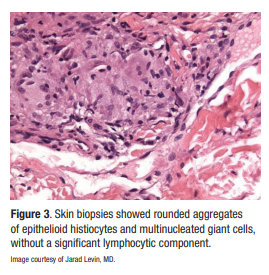

Both skin biopsies showed rounded aggregates of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells, without a significant lymphocytic component (Figure 3). Special stains for fungi and acid-fast bacilli were negative. This is classic for the “naked granulomas” associated with sarcoidosis. Additional laboratory workup showed an elevated angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) level (183, with reference normal range of 14-82). Ophthalmological consultation revealed findings consistent with sarcoid uveitis. He had just been started on mid-potency topical steroids and a concomitant systemic prednisone taper. Other agents designed for long-term maintenance, such as hydroxychloroquine, were under consideration.

Sarcoidosis is a multi-organ disease of unknown etiology that is characterized by the presence of non-caseating granulomas. Lungs, lymph nodes, and skin are the most commonly affected organs. The disease appears in higher rates in Black individuals, particularly women, ages 20-40. Sarcoidosis is often referred to as the “great imitator” because of its wide range of clinical manifestations, both on and off the skin.

Cutaneous sarcoid can include the classic lupus pernio papules and nodules on or near facial orifices, as well as ichthyosiform, psoriasiform, micropapular, ulcerative, verrucous, subcutaneous, and hypo- or hyperpigmented lesions. Erythema nodosum may be associated with sarcoidosis. An elevated ACE level is typical but because the test is sensitive but not specific, it is not a completely reliable diagnostic study. It is rare, as in this particular case, to have perfectly normal lungs, which demonstrate neither hilar adenopathy nor parenchymal disease. Only about 10% to 15% of cases have normal lungs at the time of presentation. Hypercalcemia (not found in this case) and hypergammaglobulinemia are common laboratory abnormalities.

All treatment for sarcoidosis is suppressive rather than curative. Steroids, methotrexate, antimalarial drugs, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alfa inhibitors are the most consistently reliable therapeutic interventions. Note that all therapy for sarcoidosis is “off-label,” and you may have to vigorously plead the patient’s case to secure insurance coverage for treatments such as infliximab or adalimumab.

By Ted Rosen