Intracellular parasite

With Ida Orengo, MD, and Ted Rosen, MD, FAAD

CASE HISTORY

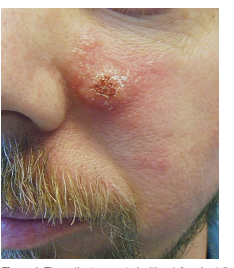

A 41-year-old male from Cuevo, Texas, (about 150 miles southwest of Houston) was referred to our facility for Mohs micrographic surgery to be performed on a squamous cell carcinoma of the left cheek.

The lesion in question had arisen three to four months prior to presentation. A biopsy done by the patient’s primary care provider and read by a general pathologist was interpreted as “atypical squamous proliferation.” The patient was in excellent health and taking no medications. He denied any travel outside the state of Texas during his entire life.

At the time of presentation, the patient had a 1.6cm by 1.5cm firm, non-tender erythematous nodule. The center of the lesion appeared to contain a keratin plug. The surgeon felt that the lesion was compatible with the keratoacanthoma subtype of squamous cell carcinoma.

However, there was some concern about the presumptive diagnosis expressed by the medical dermatologist present in the clinic that day. Namely, there appeared to be small satellite lesions at the periphery, suggesting an endemic fungal infection, such as North American blastomycosis ((Gilchrist’s disease). Nonetheless, as the original histologic slides were not available for review and the patient had driven a long distance and was eager for the lesion to be removed, Mohs surgery was performed, as planned.

Both attending physicians were shocked at the final diagnosis, which was verified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

What do you think the diagnosis turned out to be?

Histology revealed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (PEH), with the dermis containing abundant vacuolated histiocytic cells. Within these cells were tiny organisms arranged at the periphery, the so-called “marquee” sign typical of leishmaniasis. An unfixed piece of tissue was sent to the CDC, which verified this to be infection with Leishmania Mexicana. Twenty-one species of this obligate intracellular parasite can cause human disease.

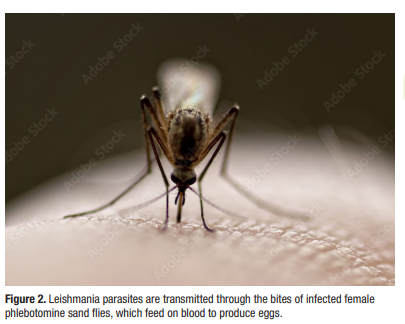

Cutaneous leishmaniasis, when it occurs in non-endemic areas, is often misdiagnosed. The diagnosis may be complicated by physicians’ lack of experience with leishmaniasis, a wide clinical differential diagnosis based solely on morphology, variable histopathologic features, and only a distant history of travel. In this case, there was absolutely no travel history, which suggests that this was a rare instance of endogenous leishmaniasis. About 50 such cases have been reported, all from either Texas or Oklahoma. It is entirely possible that the typical vector (sand fly) (Figure 2) has expanded its domain into these regions, and further similar cases may be encountered in the future.

Therapy for leishmaniasis is accomplished by administration of oral ketoconazole, parenteral pentavalent antimonials, the application of intense heat, or—most recently—use of the oral lecithin derivative miltefosine. However, there is quite varied sensitivity to drugs, and susceptibility testing (done at the CDC) is recommended. For example, only about 55% of Leishmania mexicana isolates are susceptible to miltefosine, a course of which costs in excess of $30,000. Since the lesion was ostensibly completely removed surgically, the patient declined further treatment.

By Ted Rosen, MD, FAAD