By Cheryl Guttman Krader; Reviewed by Natasha Mesinkovska, MD, PhD

Most everyone would agree that thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020 has been a pretty lousy year. How “lousy” a year it has been with respect to the prevalence of pediculosis capitis (head lice infestation) is unknown.

On the one hand, cases of head lice infestation may have become more troublesome as families spend more time together indoors. Alternatively, it is possible that cases declined because of social distancing and shifts to remote learning.

Even if there was a temporary drop in cases, it is likely that head lice remains a common problem, given its high prevalence before the pandemic, said Natasha Mesinkovska, MD, PhD, Associate Professor of Dermatology, University of California Irvine.

She notes that primary treatment for head lice generally may not be seen by dermatologists as a chief complaint for a clinic visit. However, with telehealth visits increasing, these patients may be encountered more often.

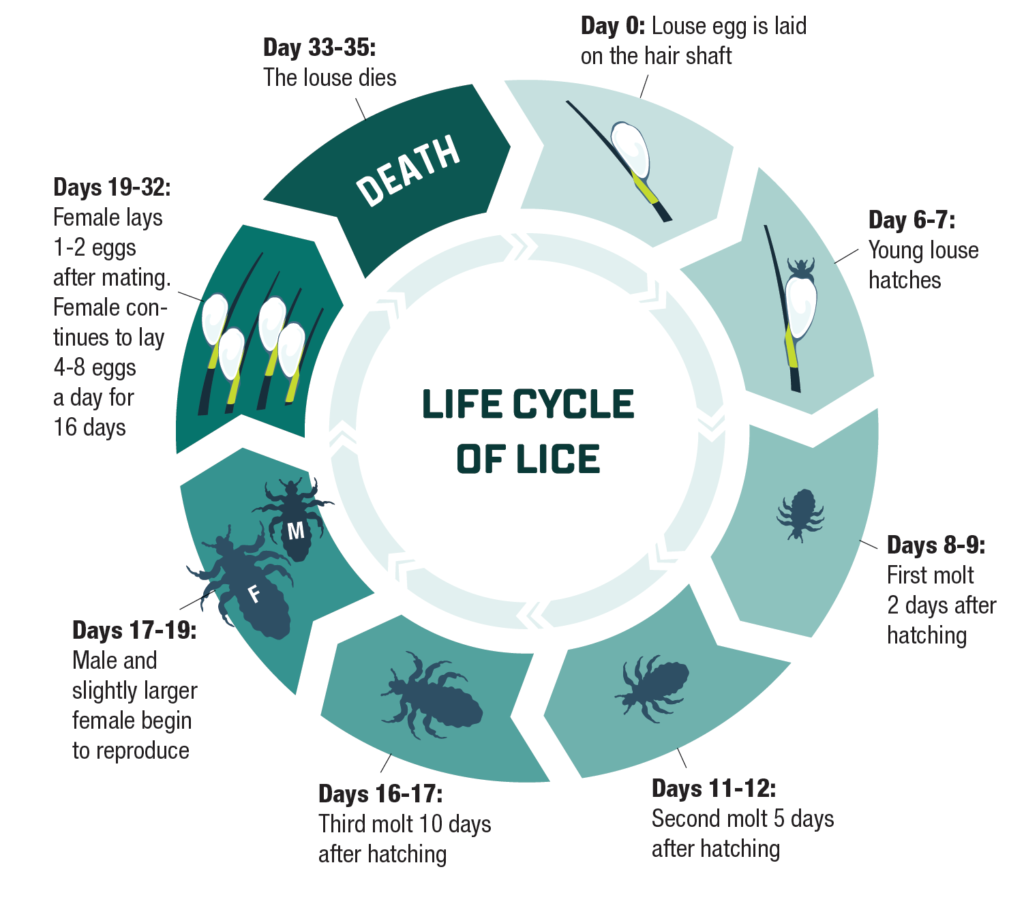

“Whether managing patients who failed previous treatment or those needing initial therapy, however, understanding the life cycle of the louse and the activity of available therapies is fundamental for successful intervention that will eradicate the infestation and prevent its spread,” Dr. Mesinkovska said.

Lice: the facts

Head lice infestation is caused by the ectoparasite Pediculosis humanus capitis, and the life cycle of this insect is comprised of 3 stages: egg, nymph, and adult.1,2 Eggs (also known as nits) are deposited and glued onto the hair shaft close to the scalp by the adult female louse. The eggs hatch after approximately 7 days, releasing the nymphs that go through 3 molts as they grow to become mature adults approximately 7 days after hatching. Then, the cycle restarts as adult female lice begin to lay 8 to 10 eggs a day during their lifespan, which lasts for approximately 30 days.

“Effective treatment of head lice requires intervention that will eradicate both the living lice and any viable eggs,” said Dr. Mesinkovska.

“Unfortunately, the active ingredients in the most commonly used OTC treatments—pyrethrin and permethrin—are associated with high levels of genetic-based louse resistance. Most are also minimally effective at eliminating the eggs. The issue of louse resistance to OTC treatment may be overcome soon, however, as the FDA granted approval for topical ivermectin lotion 0.5% to be sold without prescription.”3

Pharmacological treatments

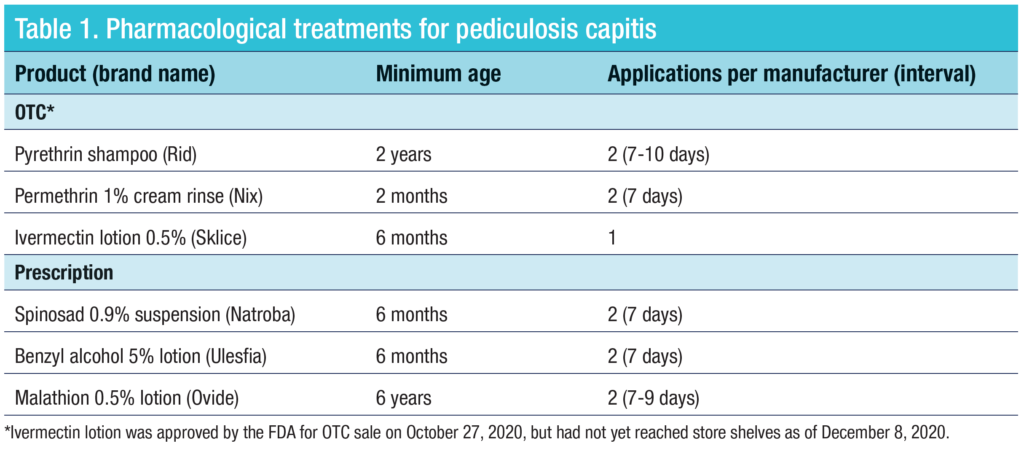

The most commonly used OTC products for treating head lice contain pyrethrin or permethrin. These chemicals act as neurotoxins to kill nymphs and adult lice, but are poorly ovicidal. “Because of these issues, permethrin and pyrethrin products need to be combined with hair combing to physically remove the nits and require repeat application 7 to 10 days after the first treatment to kill the newly hatched nymphs,” Dr. Mesinkovska said. “Adherence to these instructions, however, may be suboptimal.”

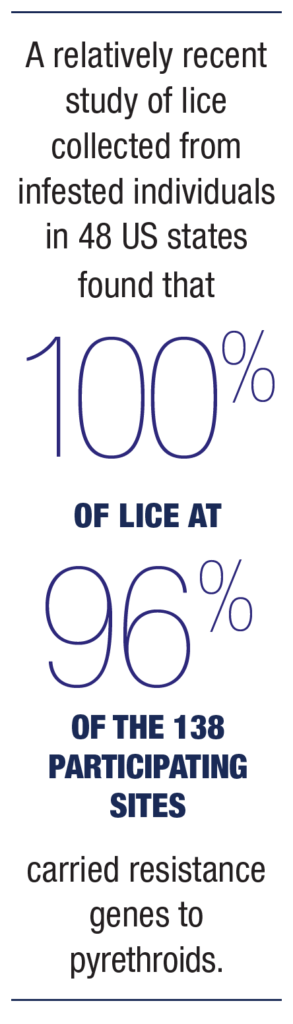

Furthermore, a relatively recent study of lice collected from infested individuals in 48 US states found that 100% of lice at 96% of the 138 participating sites carried resistance genes to pyrethroids.4 The investigators noted that the increasing frequency of the genetic mutations correlated with findings from controlled studies reporting treatment failure with products containing pyrethrin or permethrin.

Ivermectin, which has been available as a topical lotion by prescription, kills lice by neuromuscular paralysis of the insects’ feeding parts. It offers hope for more effective OTC treatment because it appears to be effective against permethrin-resistant lice.5 Although its labeling recommends a single application, Dr. Mesinkovska still advises that repeating the treatment after 7 days may be prudent.

Among the available prescription products indicated for treatment of head lice, spinosad topical suspension 0.9% is the only one that is both pediculicidal and ovicidal. Because of its dual activity, it may be a good choice for treating treatment-refractory cases of head lice, said Dr. Mesinkovska.

Malathion 0.5% is partially ovicidal, and while it has a good margin of safety, it can be irritating to skin and is not recommended for use in children younger than age 6. It must be left on the head for 8 to 12 hours after application, which may be a practical issue limiting its use.

Rounding out the prescription options is benzyl alcohol 5% lotion. Dr. Mesinskovska said she has no personal experience with that product, which acts as a suffocant.

“Some individuals may feel more comfortable using benzyl alcohol versus one of the neurotoxin-based products, but benzyl alcohol may be more irritating and still needs to be used twice because it is not ovicidal,” she said.

Non-pharmacological treatments

Patients or parents who balk at the idea of using a “pesticide” as treatment for head lice and ask for a “natural” alternative can be counseled that by definition, any chemical product designed to repel or kill lice and nits is a pesticide, regardless of its ingredients.6

“I always support finding the least toxic treatment methodology. However, claims about lack of toxicity for ‘natural’ products require substantiation, and there is little scientific evidence to substantiate efficacy for many non-pharmacological treatments, including mineral oil, coconut oil, or various essential oils,” Dr. Mesinkovska said.

If parents strongly object to using chemicals, Dr. Mesinkovska suggests trying a commercially available electric, fine-toothed metal comb intended for treating head lice (RobiComb). It runs on a single AA battery, is used on dry hair, physically removes nits, and purportedly kills live nymphs and adult lice on contact by emitting a small electrical charge.

“Efficacy of this device for treating refractory infestations was reported in a letter to the editor of the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology by dermatologist Kenneth Resnik in 2005.7 I am not aware, however, of any clinical trial evidence showing its effectiveness,” Dr. Mesinkovska said.

As another alternative to OTC or prescription pediculicides, Dr. Mesinkovska provides instructions for using a combination method of gentle skin cleanser to patients who ask about this treatment. The “Nuvo” method involves application of Cetaphil Gentle Skin Cleanser to the hair and was reported as being 96% effective by Dale Pearlman, MD, the physician who described it in 2004.8 However, the study in which it was evaluated was not a randomized, controlled trial.

Dimethicone 4% lotion is available as an OTC product (LiceMD), acts as a pediculicide through a physical mode of action, and has been reported to be effective for curing head lice and minimizing reinfestation.9

Supplemental measures

Dr. Mesinkovska believes that wet-combing the hair with a fine-toothed comb and a conditioner to remove unhatched eggs is an essential component of any effective head lice treatment regimen. Although it can even be reasonably effective as a standalone modality, with a reported cure rate of 38%,10 Dr. Mesinkovska says she does not rely solely on wet combing. Some head lice treatment products are packaged with combs, and another good option is the “LiceMeister” comb that is available for purchase online.

“Parents have to be vigilant about combing, which should be done on wet hair every 2 to 3 days for at least 2 weeks and perhaps even continued weekly for another month in younger children,” Dr. Mesinkovska said. “It is also a great diagnostic and surveillance method for re-infection.”

All family members and close contacts of a person with head lice should be checked for infestation. Although lice and eggs can be transferred onto fomites through direct contact with an infested head, the lice and eggs remain viable for a relatively short time when off the head. Although exhaustive cleaning of furniture and carpeting is probably not necessary, Dr. Mesinkovska strongly advises washing recently worn clothing, bedding, and hair-care items in hot water. In addition, plush toys should be enclosed in a plastic bag for 2 weeks or exposed to high heat in a dryer for 10 minutes.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites – Lice – Head Lice. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs). https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/lice/head/gen_info/faqs.html. Published September 1, 2015. Accessed December 7, 2020.

2. Devore CD, Schutze GE; AAP, Council on School Health, Committee on Infectious Dis. Head Lice. Pediatrics. 2015;135(5):e1355-1365.

3. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves lotion for nonprescription use to treat head lice. Published October 27,2020. Accessed December 7, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-lotion-nonprescription-use-treat-head-lice.

4. Gellatly KJ, Krim S, Palenchar DJ, et al. Expansion of the knockdown resistance frequency map for human head lice (Phthiraptera: Pediculidae) in the United States using quantitative sequencing. J Med Entomol. 2016;53(3):653-659.

5. Strycharz JP, Yoon KS, Clark JM. A new ivermectin formulation topically kills permethrin-resistant human head lice (Anoplura: Pediculidae). J Med Entomol. 2008;45(1):75-81.

6. United States Environmental Protection Agency. What is a Pesticide? https://www.epa.gov/minimum-risk-pesticides/what-pesticide. Accessed December 7, 2020.

7. Resnik KS. A non-chemical therapeutic modality for head lice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(2):374.

8. Pearlman DL. A simple treatment for head lice: dry-on, suffocation-based pediculicide. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):e275-279.

9. Kassiri H, Fahdani AE, Cheraghian B. Comparative efficacy of permethrin 1%, lindane 1%, and dimeticone 4% for the treatment of head louse infestation in Iran. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2020 Sep 12. Epub ahead of print.

10. Roberts RJ, Casey D, Morgan DA, et al. Comparison of wet combing with malathion for treatment of head lice in the UK: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;356(9229):540-544.

Disclosures

Dr. Mesinkovska has no relevant financial interests to disclose.