Rick Waalboer-Spuij, MD, PhD, with John Jesitus

Treating keratinocyte cancers including basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in medically frail patients requires looking far beyond individual lesions.

More so than in healthier patients, it requires considering the whole patient, from comorbidities and cognitive capacities to quality of life (QOL). Moreover, frail patients’ priorities may not match their doctors’ assumptions.

“One of the most important things for us as dermatologists is to realize how to recognize frail patients,” said Rick Waalboer-Spuij, MD, Ph.D., who spoke at the recent European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Spring Symposium. He is an assistant professor of dermatology at Erasmus University Medical Center (Erasmus MC) Cancer Institute in Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

“The other part is, you have to consider a lot of things. We are used to treating just spots, and you must think about the whole patient—all the comorbidities and everything—before making a plan. And that’s the most challenging part.”1

Fortunately, Dr. Waalboer-Spuij said that in recent years, dermatologists are evolving beyond the lesion-directed approach—that is, saying, “We have one basal cell carcinoma somewhere; we’ll treat it, and then see afterwards what we’ll do with the rest.”

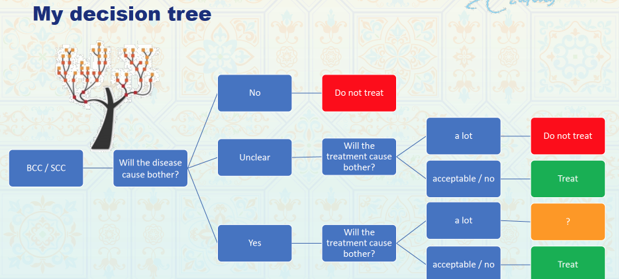

Still, said Dr. Waalboer-Spuij, deciding whether to treat or not treat keratinocyte skin cancer in a frail patient is rarely a simple yes-or-no proposition (see Figure). Key factors to consider include the patient’s age, comorbidities, cancer-related complaints, and QOL. “The majority of patients with skin cancer carry on with little to no impact on their quality of life,” he said. But for some, being diagnosed with even a single BCC can profoundly hamper QOL.

Questionnaire limitations

Many studies have concluded that BCC has little to no QOL impact.2-7 However, said Dr. Waalboer-Spuij, these studies often used generic questionnaires ill-suited to the subtleties of BCC, which is rarely life-threatening. Widely used dermatology-specific questionnaires such as the Dermatology Life Quality Index and the Skindex-17 or -29 lack the specificity to illuminate the issues that affect patients with skin cancer, he added. Even skin-cancer-specific questionnaires such as the Skin Cancer Index and the Skin Cancer Quality of Life Impact Tool suffer from methodological limitations and ignore the psychological impact of BCC and attendant behavioral changes required (avoiding sun exposure).8

To address these limitations, Dr. Waalboer-Spuij and colleagues developed and validated the Basal and Squamous Cell Carcinoma Quality of Life (BaSQoL) Questionnaire.9 Previous questionnaires tended to examine QOL during a defined period such as the previous week or month, said Dr. Waalboer-Spuij. “But we noticed that skin cancer patients often get more than one. And the first one can make a big impression. So, it’s important to ask if there’s a difference between before and after the first diagnosis.” Accordingly, the BaSQoL’s 16 questions address feelings at the time of diagnosis and treatment, the impact of skin cancer during the past week, and behavioral changes.

Along with QOL metrics, said Dr. Waalboer-Spuij, the concept of frailty is useful in considering what impact treatments will have on the elderly and other patients. “Frailty is a combination of aging, having a chronic disease, and having reduced spare capacity.10 You must be careful not only to look at age but also much more.”

In an actinic keratosis (AK) study on which Dr. Waalboer-Spuij was senior author, even the youngest group, 50-59 years, included a potentially frail patient.11 Moreover, on both skin-specific (Skindex-17) and disease-specific (Actinic Keratosis Quality of Life) scales, frail patients experienced QOL disruption at the time of treatment, while non-frail patients did not.11 The differences were not statistically significant, Dr. Waalboer-Spuij said, but the results show that even noninvasive topical AK treatments can hinder QOL. More worrisome, he said, is that for frail patients, this disruption lasted several weeks post-treatment. “When you have frail patients, you must consider even more carefully what the impact of your treatment will be.”

Assessing patients fully

At Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, the process begins with preprocedural geriatric assessments performed by geriatricians for potential frail patients. Along with a physical examination, assessments include questionnaires such as the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale, the Mini-Mental State Examination, and the Outcome Prioritization Tool (OPT; optool.nl). The last of these, developed in 2011 in the United States and tested in the Netherlands,12,13 is available in Dutch and English.

Using vertical sliders, the OPT asks patients to rank 4 priorities:

- Staying alive

- Maintaining independence

- Reducing pain

- Reducing other symptoms

No categories’ scores can be equal, said Dr. Waalboer-Spuij, which forces patients to prioritize. “This helps to discuss with the patient what’s the most important thing for him or her. It can be surprising.”

When someone presents at the university clinic with a diagnosis, he explained, “it’s easy to assume that the patient wants treatment.” But sometimes, Dr. Waalboer-Spuij said, patients have other priorities.

One such case involved an 82-year-old man who presented at the university’s multidisciplinary clinic with a large, invasive SCC of the ear. Surgery would have required removing the ear, part of the middle ear, and a large section of skin behind the ear where the tumor had spread. But for the patient, who was frail, obese, and had other comorbidities, general anesthesia would pose significant risk. Even multiple radiotherapy appointments would have caused hardship. And the patient refused to enter a nursing home because he prioritized staying home as long as possible.

“We decided as a group, together with the patient and his son, that surgical treatment would only make his current situation worse. So, we decided with his general practitioner only to do something about his complaint, which was pain,” said Dr. Waalboer-Spuij.

Teaming up with other specialists

In making complex medical decisions, Dr. Waalboer-Spuij advised including as many people as necessary. Erasmus MC Cancer Institute conducts a weekly multidisciplinary skin cancer meeting that includes 9 specialties ranging from dermatology to radiation oncology, head and neck surgery, and geriatrics. This group discusses approximately 800 patients with difficult or locally advanced skin cancer—including melanoma and Merkel cell carcinoma—per year.

Commonly, he said, institutions conduct separate meetings for melanoma, head and neck cancer, and other skin cancers. “We’ve combined all types of skin cancer in one meeting, and we bring all the involved specialists to that meeting so we can efficiently discuss those patients and learn from each other.”

The meeting’s main message, said Dr. Waalboer-Spuij, is to think before acting, particularly when treating frail patients. “Discuss with the whole team what the options are. Sometimes we forget that doing nothing, or palliative pain treatment, is also an option.”

REFERENCES

1. Waalboer-Spuij R. Management of NMSC in frail patients. European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Spring Symposium. May 6, 2021.

2. Blackford S, Roberts D, Salek MS, Finlay A. Basal cell carcinomas cause little handicap. Qual Life Res. 1996;5(2):191-194.

3. Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Quinn LM, Covinsky KE. Convergent and discriminant validity of a generic and a disease-specific instrument to measure quality of life in patients with skin disease. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;108(1):103-107.

4. Roberts N, Czajkowska Z, Radiotis G, Körner A. Distress and coping strategies among patients with skin cancer. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2013;20(2):209-214.

5. Rhee JS, Matthews BA, Neuburg M, et al. Skin cancer and quality of life: assessment with the Dermatology Life Quality Index. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(4 Pt 1):525-529.

6. Chren MM, Sahay AP, Bertenthal DS, et al. Quality-of-life outcomes of treatments for cutaneous basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127(6):1351-1357.

7. Sampogna F, Spagnoli A, Di Pietro C, et al. Field performance of the Skindex-17 quality of life questionnaire: a comparison with the Skindex-29 in a large sample of dermatological outpatients. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(1):104-109.

8. Waalboer-Spuij R, Nijsten TE. A review on quality of life in keratinocyte carcinoma patients. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013;148(3):249-254.

9. Waalboer-Spuij R, Hollestein LM, Timman R, et al. Development and validation of the Basal and Squamous Cell Carcinoma Quality of Life (BaSQoL) Questionnaire. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98(2):234-239.

10. Xue QL. The frailty syndrome: definition and natural history. Clin Geriatr Med. 2011;27(1):1-15.

11. Bussink BE, Elling R, Houwing RH, Waalboer-Spuij R. Actinische keratose bij (kwetsbare) ouderen: wel of niet behandelen? Ned Tijdschr Dermatol Venereol. 2021;1:46-49.

12. Fried TR, Tinetti M, Agostini J, et al. Health outcome prioritization to elicit preferences of older persons with multiple health conditions. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83(2):278-282.

13. Schuling J, Sytema R, Berendsen AJ. Aanpassen medicatie: voorkeur oudere patiënt telt mee [Adjusting medication: elderly patient’s preference counts]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2013;157(47):A6491.

DISCLOSURES Dr. Waalboer-Spuij reports no relevant