Brett C. Neill, MD, with Mary Beth Nierengarten

Dermatologist

University of Kansas Medical Center,

Kansas City

Improving the care of patients with dermatologic conditions relies on multiple factors—access to care, a correct diagnosis, a reasonable and effective treatment plan, and appropriate follow-up. Clinical expertise, experience, and judgment are what dermatologists offer their patients to fulfill these factors, but what if a patient doesn’t understand the words used to describe his or her condition, treatment plan, or prognosis?

Lack of health literacy, studies suggest, is linked to less use of health care services and poorer outcomes.1 Conversely, data show high health literacy may be linked with better outcomes due to, for example, greater treatment adherence.2 However, as noted in the Healthy People 2020 report by the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, health literacy is complex, and a person with high overall literacy may still have low health literacy.3

A recent study at the University of Kansas Medical Center underscores the complexity of health literacy.4 Conducted to compare the confidence patients had in their understanding of frequently used terms in dermatology versus the true accuracy of their understanding, the study found that patients with higher education and confidence tended to overestimate their understanding of common dermatologic terms.

In the multicenter study, 313 adult patients recruited from academic dermatology clinics completed a survey reporting their confidence in understanding 11 commonly used terms in dermatology. Using a 5-point Likert-type scale, patients rated their perceived confidence in understanding each dermatologic term. Two blinded physicians then used a 5-point scale to grade the accuracy of each patient’s perceived understanding.

The study found that women, patients with a higher level of education, and those with more experience in the medical field reported a higher perceived understanding of the dermatologic terms compared to men, those with lower education levels, and those without medical experience.

However, those with a higher perceived understanding were also more likely to overestimate their knowledge—meaning that these patients perceived their understanding to be higher than their actual understanding as graded by the physicians.

This suggests that providers should always use patient-friendly terminology and not assume patients will understand, regardless of demographics.

Clinical implication for dermatologists

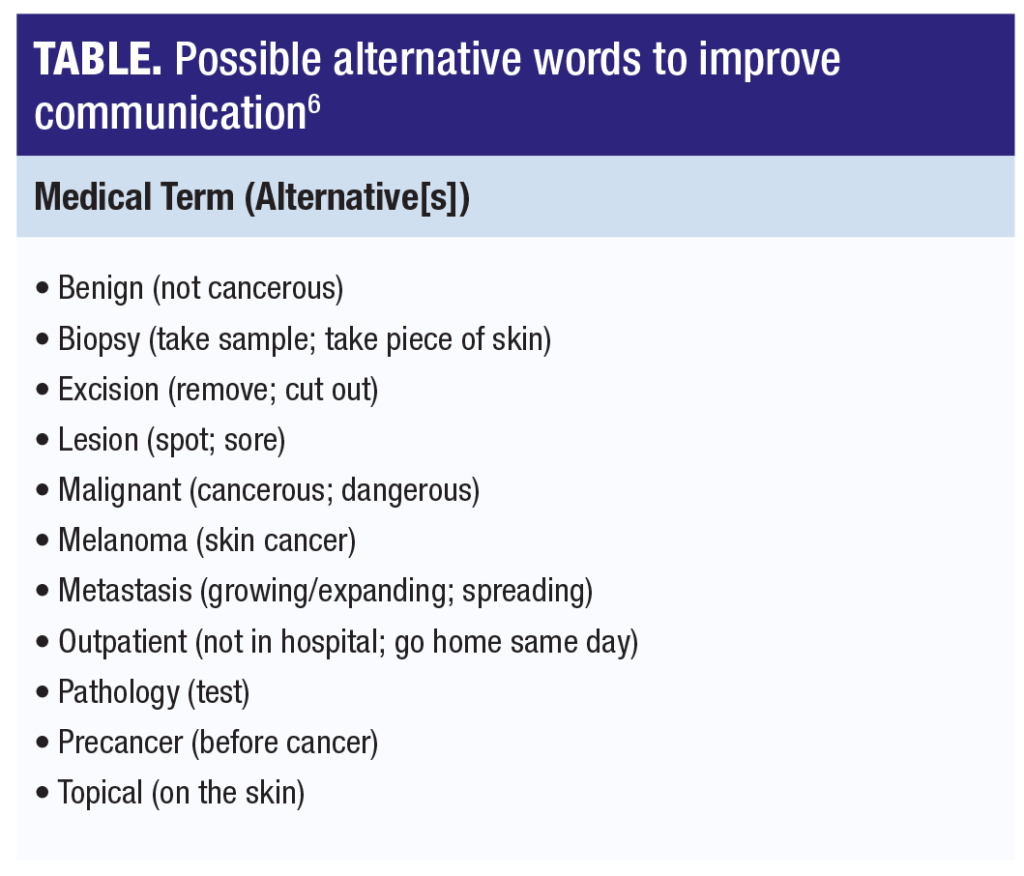

One clear message to dermatologists is to use simple, jargon-free language with all patients. Among the 11 commonly used dermatologic terms included in the study, the terms for which patients reported the lowest confidence in understanding were “metastasis,” “pathology,” and “excision.” The terms patients were least accurate in defining were “lesion,” “pathology,” and “metastasis.”

Dermatologists need to bear in mind that patients that express confidence in understanding terms used may be at particular risk of not receiving accurate information because these patients may be less likely to ask for clarification. This may be less of a problem with patients who report less confidence in understanding terms. Fortunately, patients with lower education and those without medical experience were less likely to overestimate their knowledge.

A more recent study by Sanchez and colleagues underscores the importance for dermatologists not to overestimate

patient understanding of commonly used terms.5 In the study of 285 patients recruited from outpatient dermatology clinics in the Boston area, patients completed a survey on dermatologic-specific words. A questionnaire was also completed by 70 providers on their perception of patients’ understanding of these words. Notably, the study included a high percentage of minority and non-English-speaking patients (46% were Hispanic/Latino) as well as lower-income populations (40%).

The study found that more than 50% of patients did not understand the terms “autoimmune,” “hyperpigmentation,”

“metastasis,” and “excision.” In addition, the study found that providers overestimated patient comprehension on a

number of common terms: “benign,” “sunburn,” “symptom,” “scar,” and “recur.”

Of the 70 providers, 66 cited “lack of time” as the major barrier to communication but only 7% thought that spending more time with a patient would improve communication.

Effective communication: make it simple and clear

In a reply to the Sanchez et al study, my colleagues and I emphasized the need for low-cost, simple strategies that

can be adopted widely, particularly for vulnerable populations for whom low health literacy can exacerbate health

disparities. One way to improve communication with patients is to use alternative words that patients themselves

provide (Table).

In addition to alternative terms, easy-to-read patient handouts simplify treatment plans and after-visit summaries.

However, some premade resource materials for patients on the internet are written above the recommended 6th-to-8th-grade reading level, so further clarification of these materials may be needed.

Finally, nurses can be helpful when conveying information to patients. Having a nursing staff that can provide brief

end-of-visit summary sessions gives patients a platform to ask questions and seek clarification. This can help overcome the barrier of limited time cited by providers as the main obstacle to better communication with patients.

REFERENCES

- Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, et al. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(2):97-107.

- Miller TA. Health literacy and adherence to medical treatment in chronic and acute illness: a meta-analysis. Patient Edu Couns. 2016;99(7):1079-1086.

- Health Literacy. Healthy People 2020. US Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-health/interventions-resources/health-literacy

- Neill BC, Golda N, Seger EW, et al. Determining patient understanding of commonly used dermatology terms: a multicenter cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(3):933-935.

- Sanchez D, McLean EO, Maymone MB, et al. Patient-provider comparison of dermatology vocabulary understanding: a cross-sectional study of patients from minority ethnic groups. Arch Dermatol Res. 2020;312(6):407-412.

- Neill BC, Seger EW, Rickstrew JJ, Rajpara A. Reply to “Missing the mark on patient comprehension.” J Am Acad Dermatol. (online) 2021;84(2):E117-E118

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Neill reports no relevant financial interests.